During my doctoral research I worked, struggled and fought with three different languages: Italian, English and German. Or to put it more positively, I was privileged to have the opportunity to step out of my comfort zone on a regular basis.

The language of my research was Italian, as most of the archival documents were in Italian. I had a solid knowledge of the language from school and progressed during my time in Rome, and although I wouldn’t call myself fluent, I was able to conduct most of my interviews in Italian. English was the language in which I usually presented and communicated my research, as it is the lingua franca of science and architecture in particular. However, I decided to write my thesis in my mother tongue, German, for pragmatic reasons, but also for the sake of thoroughness. I defended my thesis on 4 October 2023, ironically the first and so far only time I have presented my research in German.

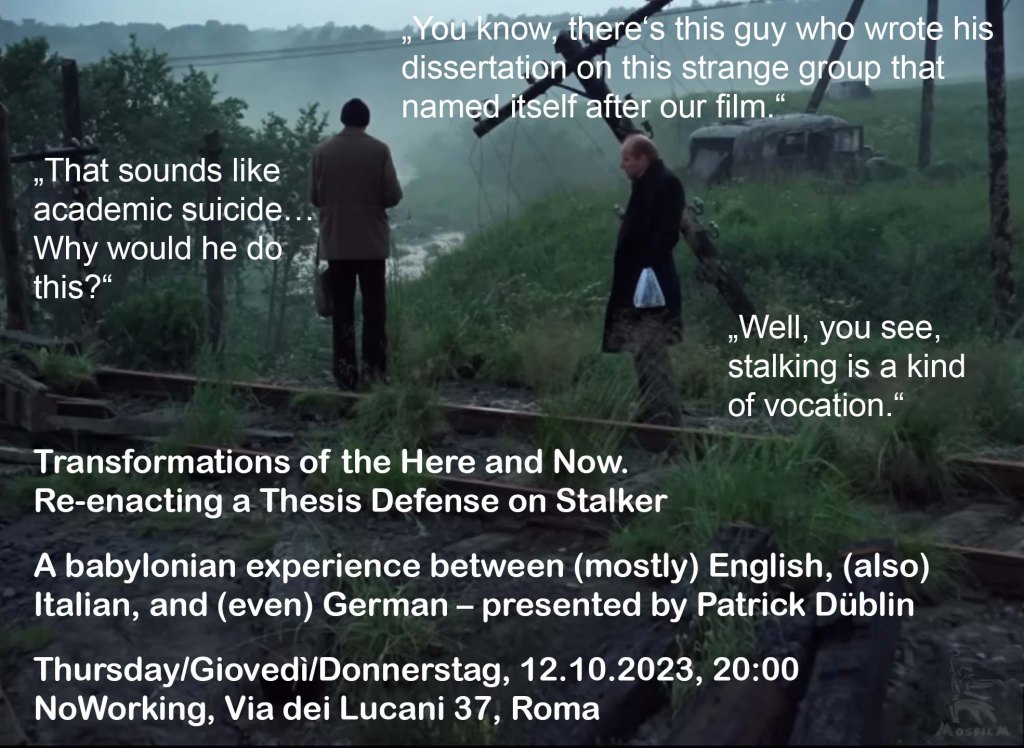

Soon after, I was on my way to Rome, where I wanted to playfully re-enact my dissertation defence. There were Italians in the audience as well as a group of art students from the University of Linz in Austria. This fact and the aforementioned language triangle motivated me to use translation as a theme for the re-enactment and to actively engage in a Babylonian experience.

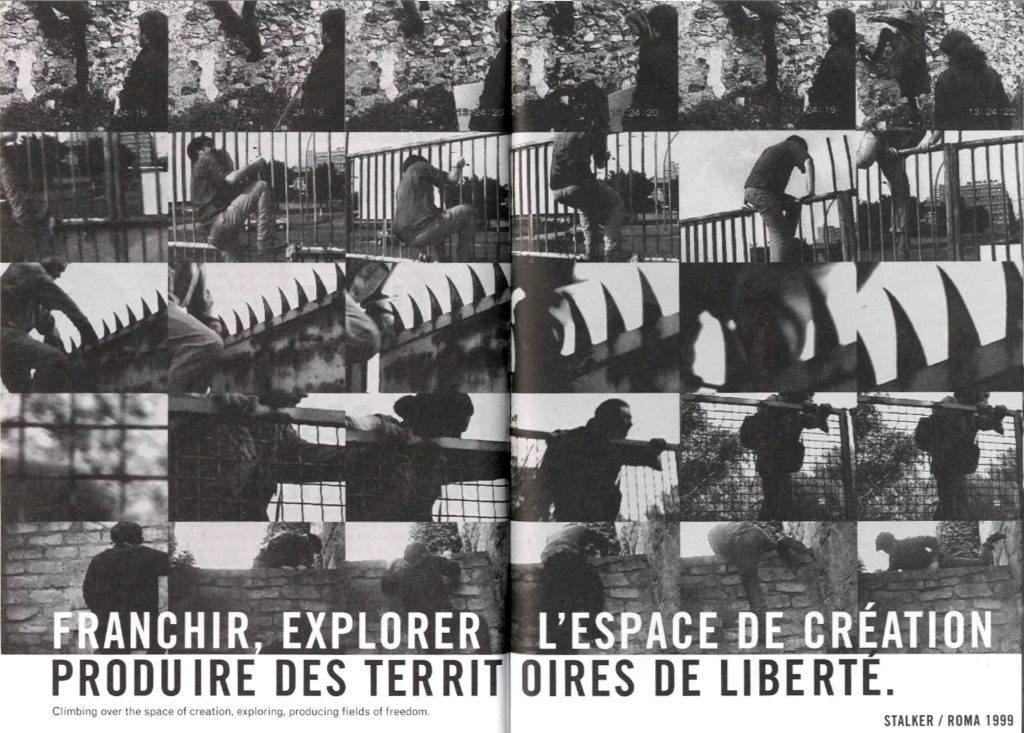

I had prepared a handout with Christian Morgenstern’s poem “Der Lattenzaun” in the original German, with an official English translation and a very rough Italian translation of my own. I began by reading the poem in German, followed by my conclusion in Italian, pointing out the similarities between the poem and the practice of the Stalker group: the centrality of interstitial spaces (Zwischenräume), their habit of performatively reinterpreting fences and borders, an unconventional understanding of doing architecture, etc.

Using the same slides from my original defence, I had my German script in front of me, which I translated directly into English during the presentation. Finally, I had brought a preliminary manuscript of my dissertation, which contained English and Italian quotations alongside the main German text. I asked one of the Austrian art students to select and read a German paragraph, then an Italian speaker to read a quotation in Italian. Using English again as a bridge language, I then attempted to connect the two random passages, weaving a narrative in line with the outcome of my research and raising open questions about the practice of the Stalker collective in general.

Like most events at the NoWorking space, my talk was followed by a cozy dinner, where once again languages were mixed like a salad.

To make up for the terrible Italian translation of the (actually not easy to translate) poem by Morgenstern, I’m concluding this retrospective impression with one of my favorite Italian words: lo scavalco. It literally means “the act of climbing over,” and this clumsy paraphrase already demonstrates that the term is not translatable into English – or German, for that matter. But in order to talk about Stalker’s practice, lo scavalco is essential, since the group’s performative interventions are usually triggered by an initial act of crossing a boundary. What can easily be misinterpreted as an expression of male heroism is actually a means of entering new territory. As such, it is a metaphor for a learning experience.

Foreign languages, too, are first and foremost invitations to climb over.

Leave a comment