We live in nostalgic times. Technologies are changing, economies are stagnating, wars are raging, and the effects of climate change are being felt. Faced with these circumstances, many people choose not to adapt to these challenges, but to ignore or even deny them, wishing for a return to a mythical golden age that apparently once was.

I have never been a fan of psychoanalysis, but these desires strike me as an impossible need to return to childhood, perhaps even to a prenatal state, the comforting and protective bubble that shielded us from the influences of the outside world. Life as a fetus was undoubtedly easier because we didn’t have to think for ourselves. Instead, a strong leader decided for us.

But even in less political contexts, “going back” can be treacherous. I tried it once and it ended badly.

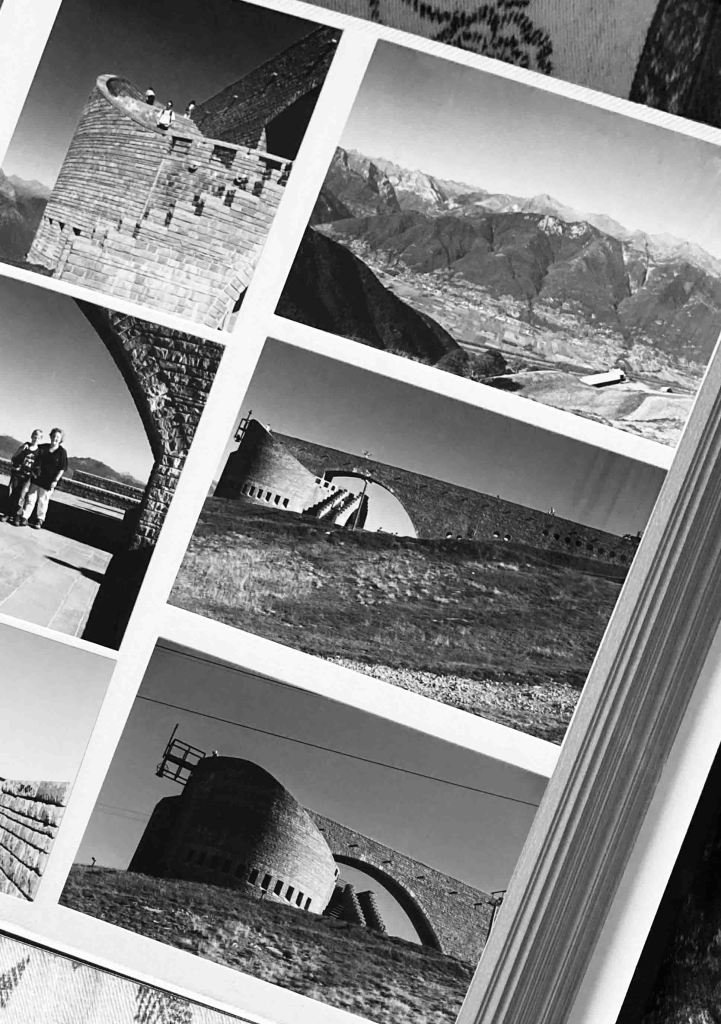

In 1997, I visited Mario Botta’s Chapel of Santa Maria degli Angeli on Mount Tamaro in Ticino, the Italian part of Switzerland. The building, located at an altitude of 1530 meters, had been completed only a year earlier, and my parents decided to visit it. For me, an eleven-year-old boy, the experience was my first encounter with the sublime, and it sparked an enduring fascination with architecture and landscape.

The chapel itself is a modest space in Botta’s characteristic round tower language. However, the architect decided to make a spectacle of it by connecting it with a long, aqueduct-like bridge that can be walked on. Following this straight corridor, one gradually detaches oneself from the topography and approaches the innumerable peaks of the Alps and the eternal celestial sphere above. At the end of this journey, one arrives at a suspended metal structure that offers an unobstructed view of the Alpine valley. Towering at these heights is an almost spiritual experience. And the architectural promenade reinforces this feeling by adding a processional element. That was the first time I realized what architecture can do when it is designed to resonate with both the environment and the user.

So much for that pivotal architectural experience in the age of innocence. 21 years later, I returned to the site. Not explicitly to reconnect with the wonders of my childhood, but neither could I ignore the powerful impression it had made on my first visit. So the stakes were high – and so was my disappointment. The impossibility of reliving an extraordinary past experience was not the point. I was old enough to know the dangers of nostalgia. The source of my disappointment was the way the place had changed. In 1997, there was only the chapel, a monolithic porphyry-clad structure on the green hillside. But now the place had turned into an amusement park. There was a toboggan run, a sculpture trail and, worst of all, an ugly prefabricated restaurant right next to the Botta Chapel.

The canton of Ticino has a history of relatively lax building regulations, and perhaps that is why a monumental chapel far from civilization was possible in the first place. But then the tourist industry took advantage of the freedom to build and the lack of aesthetic standards and eventually ruined the place. At least from the perspective of my childhood experience. It was a lesson: the golden era of a mythical past may appear like a sublime temple on a pristine green meadow on a mountaintop. But those who try to access it will find only a pale and corrupt imitation of that desire.

Yet the present is not all bad. (As the future past, it may actually turn out to have been the best of all times.) Comparing past and present might even help us to re-examine our beliefs. For example, is the monolithic building in the landscape still a form of architecture we can support? How can we reconcile the monumental and the functional, the sacred and the secular?

Not far from Botta’s monument to the sacred and the sublime is this monument to the mundane. Situated in a similar place, but realized with much simpler means, it could even be read as an anti-architectural counterproposal to the Chapel of Santa Maria degli Angeli. In this respect, the processional element is replaced by a communal ritual: instead of walking individually towards eternity, this “holy site” provides the infrastructure to break bread, to share a meal at the edge of infinity.

Who knows, maybe the local preservationists will soon start a beautification project and replace the bench and trash can with solid granite structures. And I will visit them again as an old man, nostalgic for the simplicity of the original version.

Leave a comment