‘Gonk’ is the Serbian word for arcade or porch, and refers to a key feature of elongated single-storey houses built in the 19th and early 20th centuries, usually in classicist or neo-baroque style. These traditional Vojvodina Houses are ubiquitous in northern Serbia, as well as in southern Hungary and western Romania. They are the product of Austro-Hungarian planning regulations, German settlers, and local knowledge and materials.

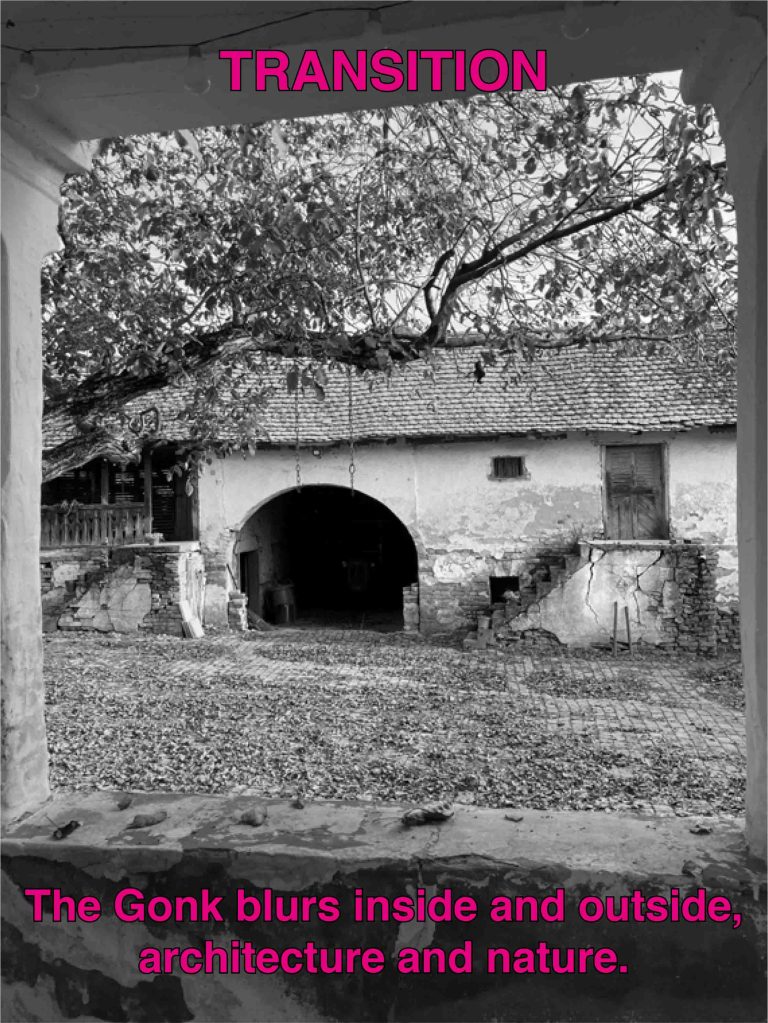

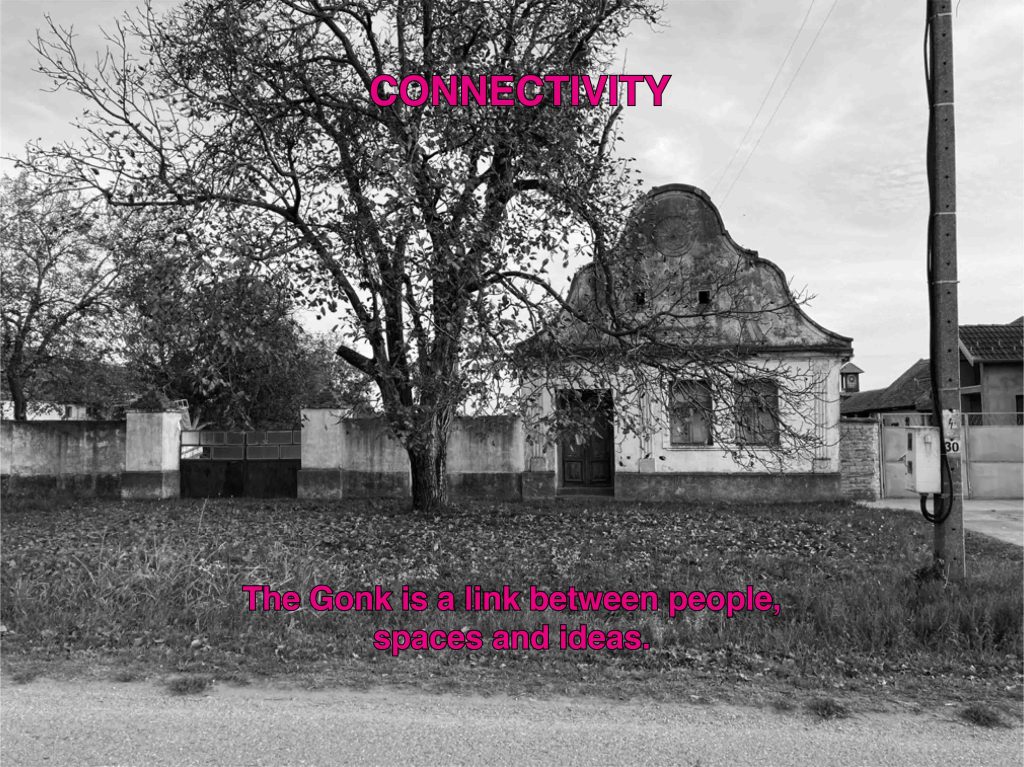

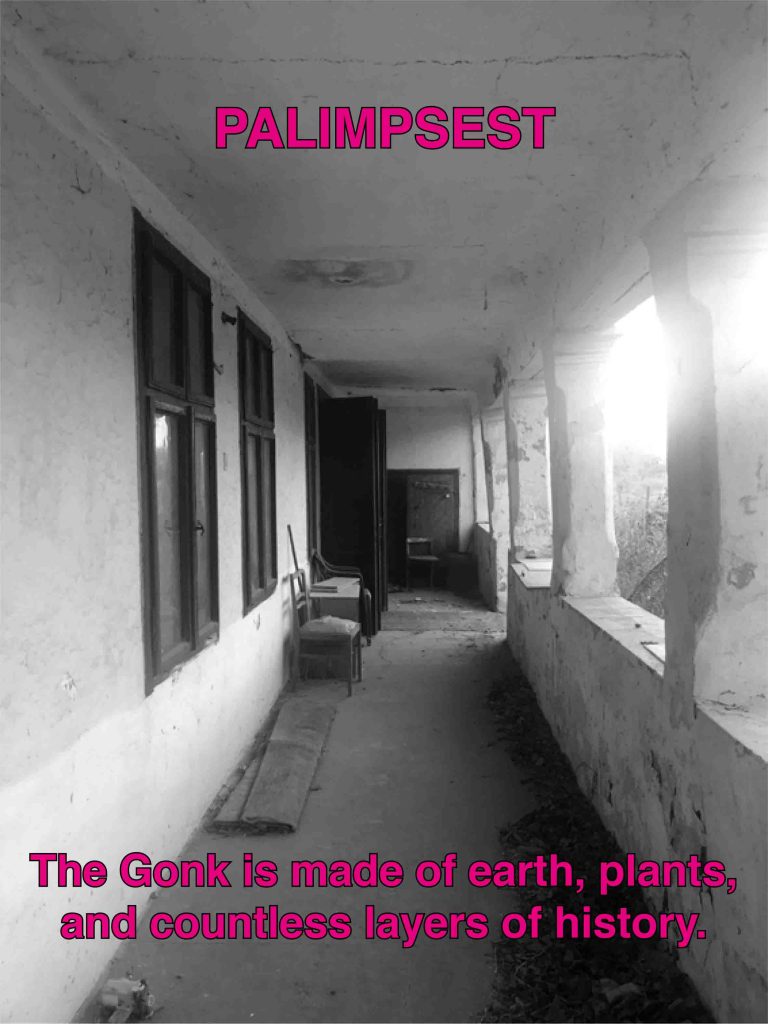

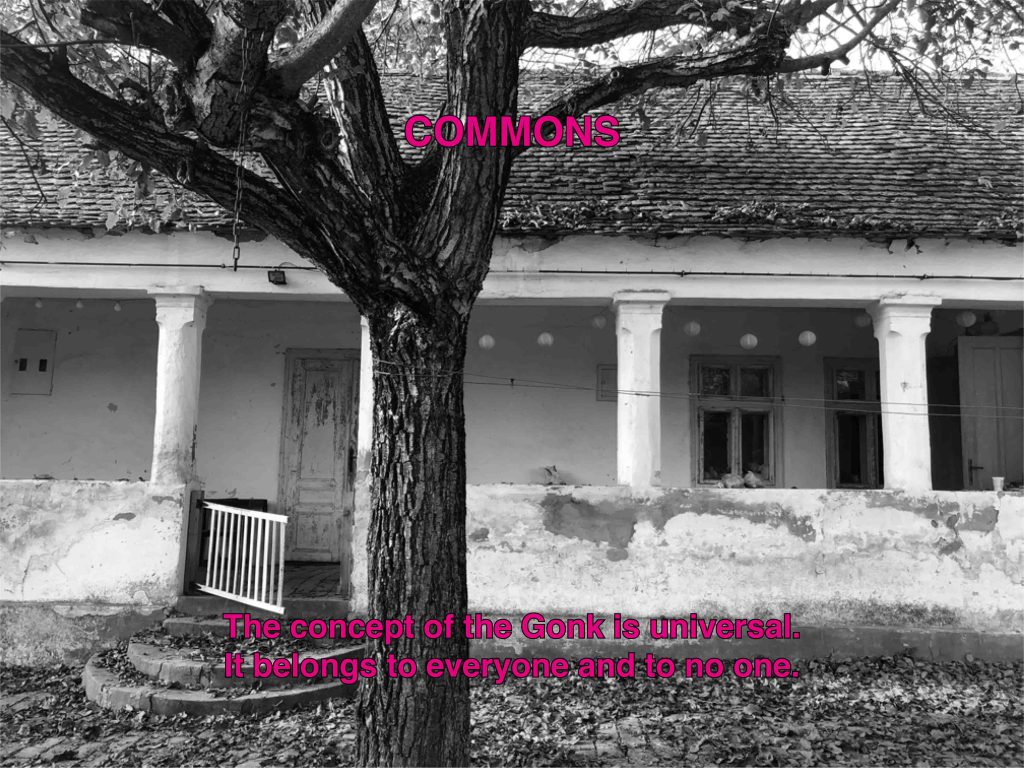

The Gonk provides a built interface between open space and enclosed architecture. As such, it embodies a threshold between inside and outside, architecture and nature, private and public spheres. It is also a place of social and climatic transitions: working and living, activity and rest, hot and cool, wet and dry. Above all, the Gonk is also a cultural threshold. Its origin cannot be attributed to a single nationality or ethnicity. It is foreign and vernacular at the same time. As a result, it embodies a melting pot of cultures, histories and techniques. It is a palimpsest of past knowledge waiting to be rediscovered.

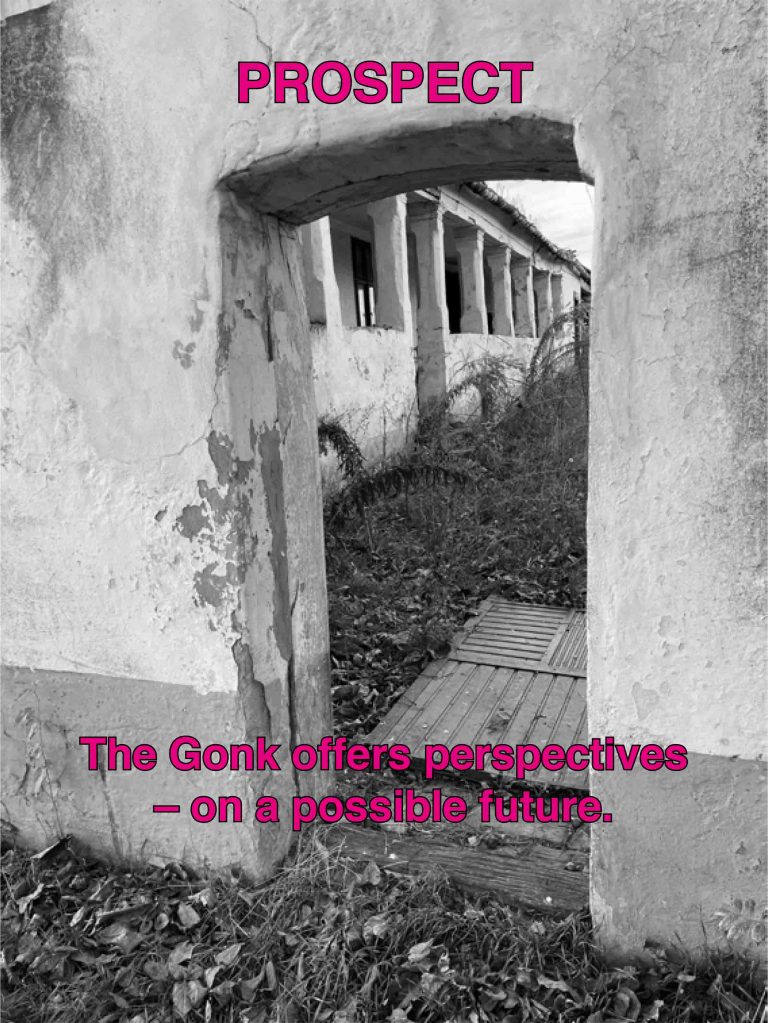

For the open competition for the contribution of the Serbian Pavilion to the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025, Stanislava Predojević and I proposed the Gonk as a prism that can concentrate the complexities of the past and illuminate approaches to the challenges of today. In this way, we see the Gonk as a manifesto: A call to invite your neighbours, to gather, to enjoy the benefits of both shelter and exposure, and to reflect on living in a threshold space. The Gonk penetrates and connects times, spaces and people. It is a gateway not only to the house itself, but also to knowledge about sustainable building materials and intercultural exchange.

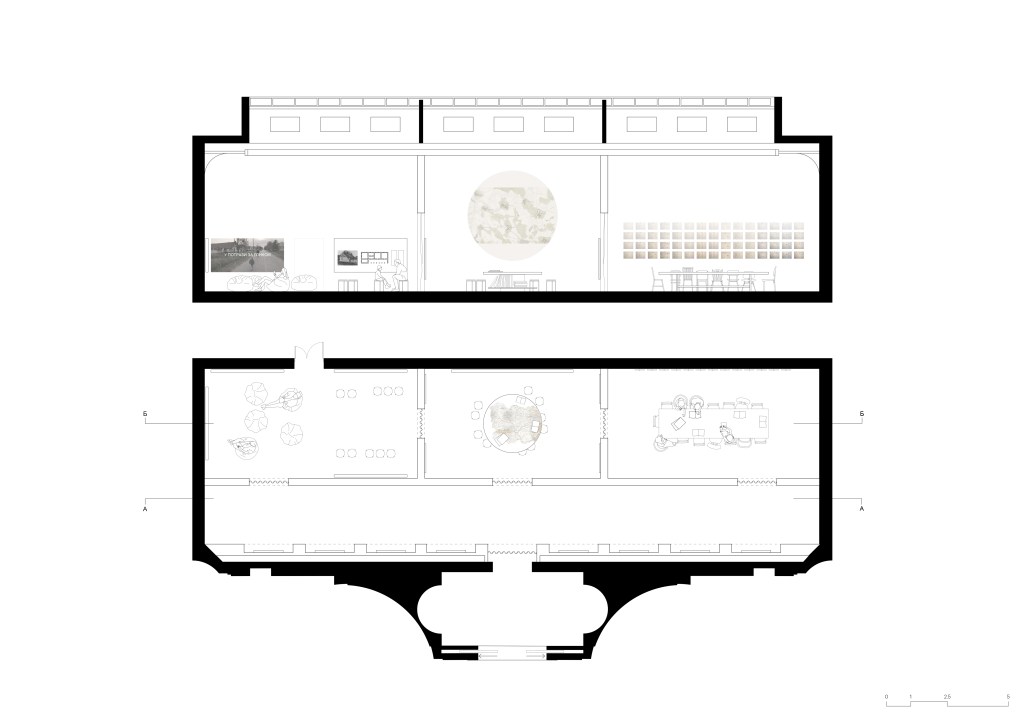

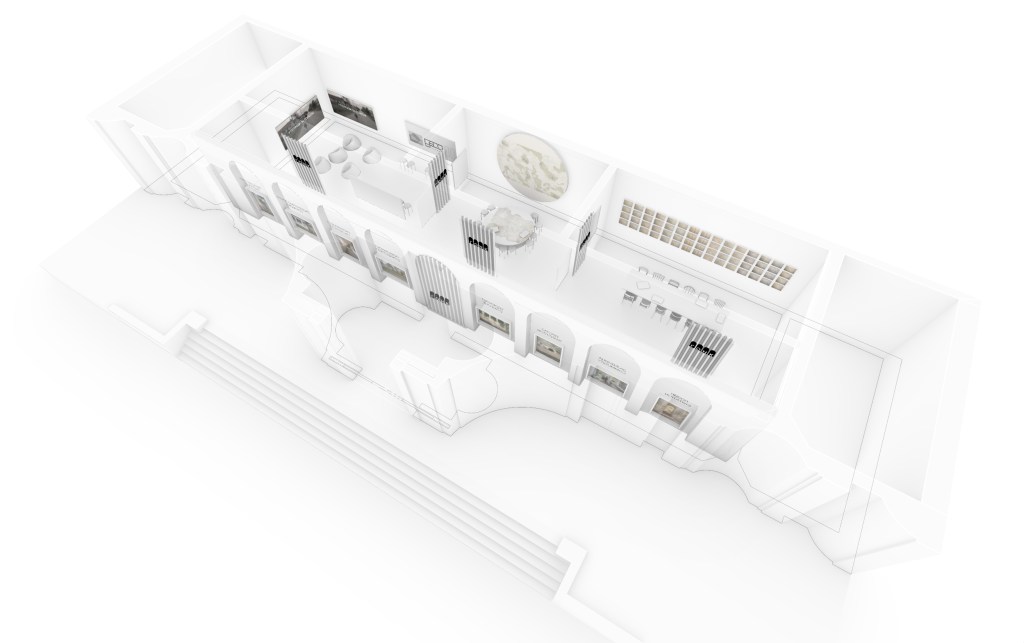

The layout of the exhibition follows the three-room organisation of the Vojvodina House, starting with an oversized version of the Gonk with suggested arches, each illustrating a paragraph of the Manifesto, accompanied by an evocative image on a light box.

The middle room, the ‘kitchen’, is the central node where histories, geographies, languages and urbanisms converge. A round table symbolically gathers these differences and layers, accentuated by a variety of documents, plans and literature in Serbian, German, Hungarian and Romanian.

The left room, the ‘living room’, represents domestic life. Here visitors can immerse themselves in a photographic archive of Vojvodina Houses and their uses. It is the result of a public call for historical and contemporary photographic documentation. In addition, a film shows life in and around the Gonk in various locations.

The room on the right is the ‘guest room’, often called čista soba (clean room) in Serbian. There, on a long table with pens and sheets of paper, visitors of all ages are invited to draw their suggestions, wishes and desires for Gonk and the Vojvodina House. Afterwards, the drawing can be hung on the wall, creating an analogue and constantly updated database of ideas.

The exhibition builds on the Gonk’s traditional purpose as a platform for social gatherings by proposing it as an agora where people can stroll, converse, debate, and also forge their vision of tomorrow. In this way, it encourages participatory collaboration and collective intelligence.

By drawing lessons from a historical example, the exhibition will offer perspectives on contemporary challenges such as social alienation, cultural boundaries and climate change. It will contribute to current architectural discourses such as re-use, built heritage and sustainability. Most importantly, it will ask people themselves what perspectives a view through the Gonk offers, what questions it raises and what desires it inspires.

Leave a comment