To me, Japan is a bit like Kafka’s Castle: attractive yet ultimately unreachable. However, I recently had the opportunity to present my research on Stalker’s practice to a group of students at Kyoto Institute of Technology, albeit remotely. Matthias Vollmer, an associate professor at the institute, invited me to speak at his design studio in which students were tasked with reimagining one of the many green and residual spaces on campus.

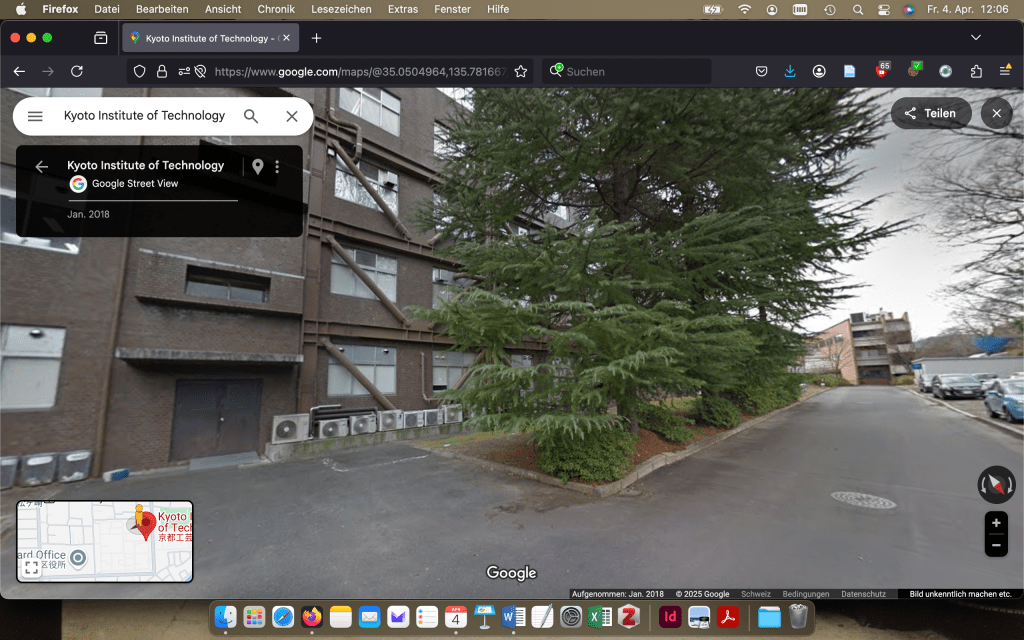

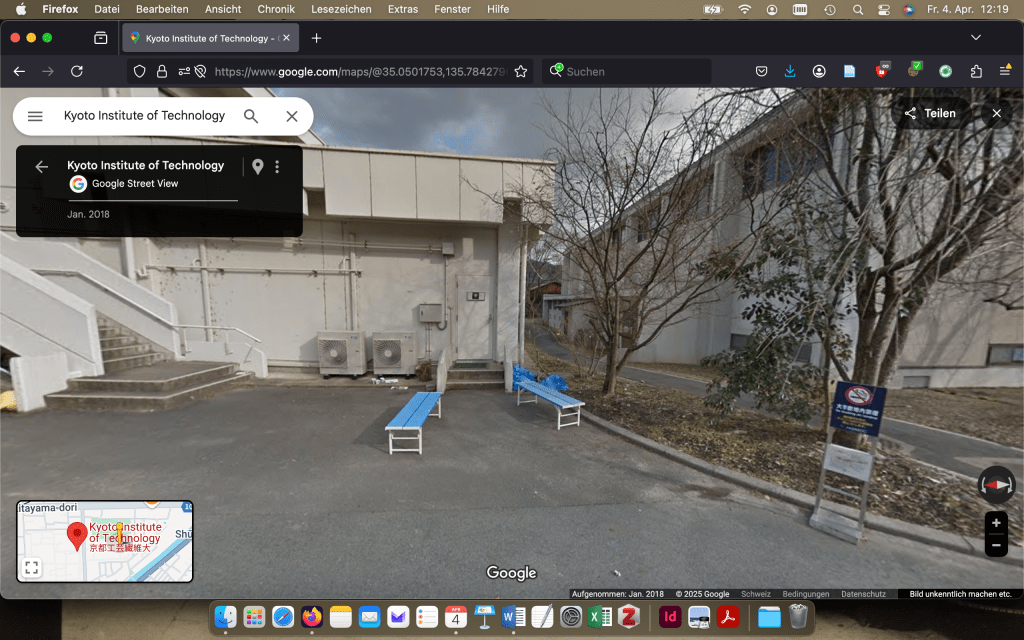

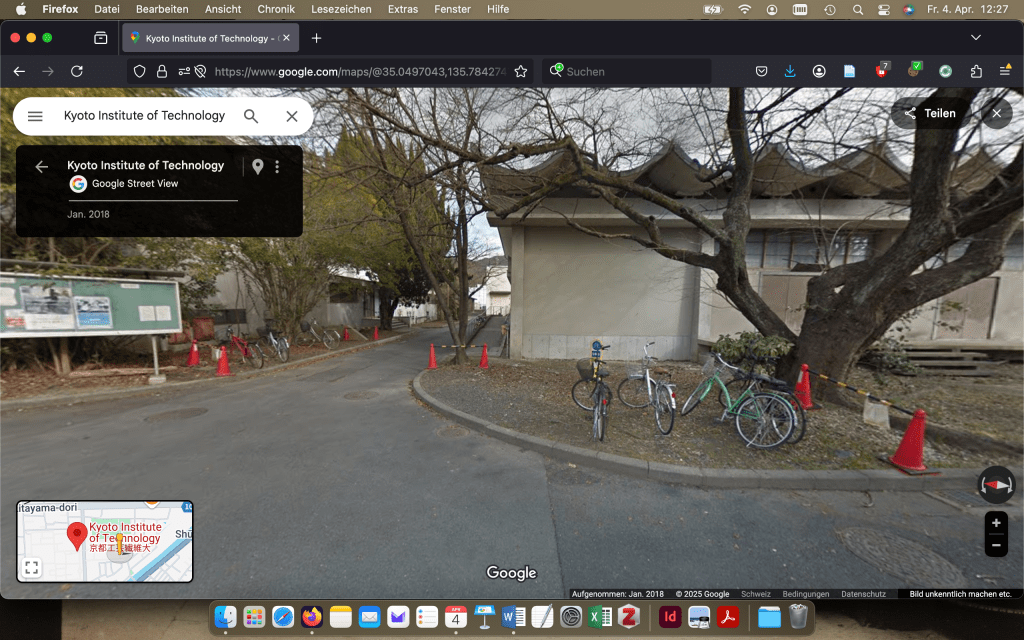

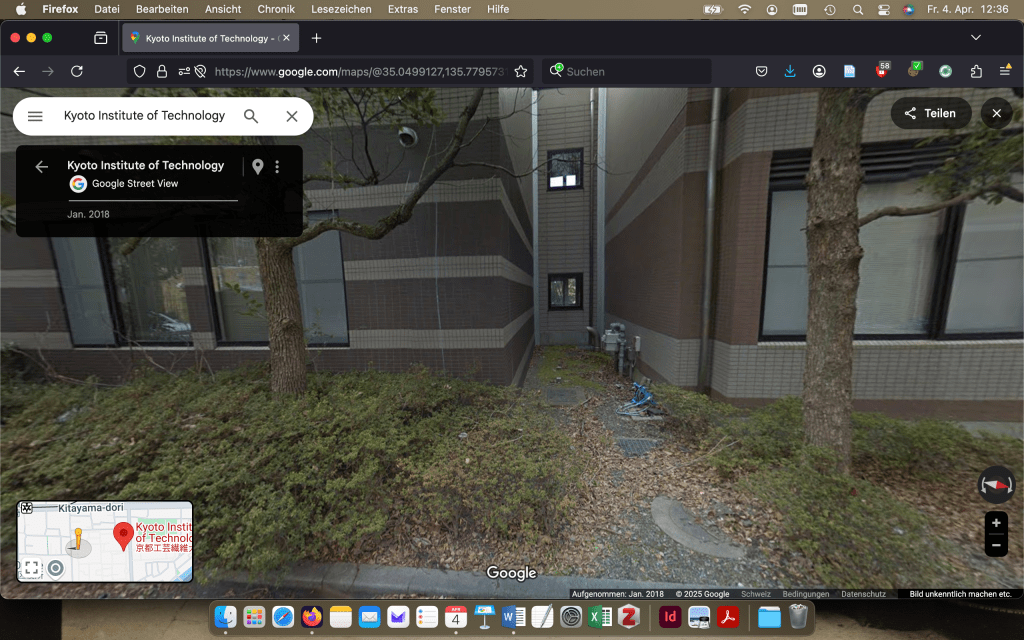

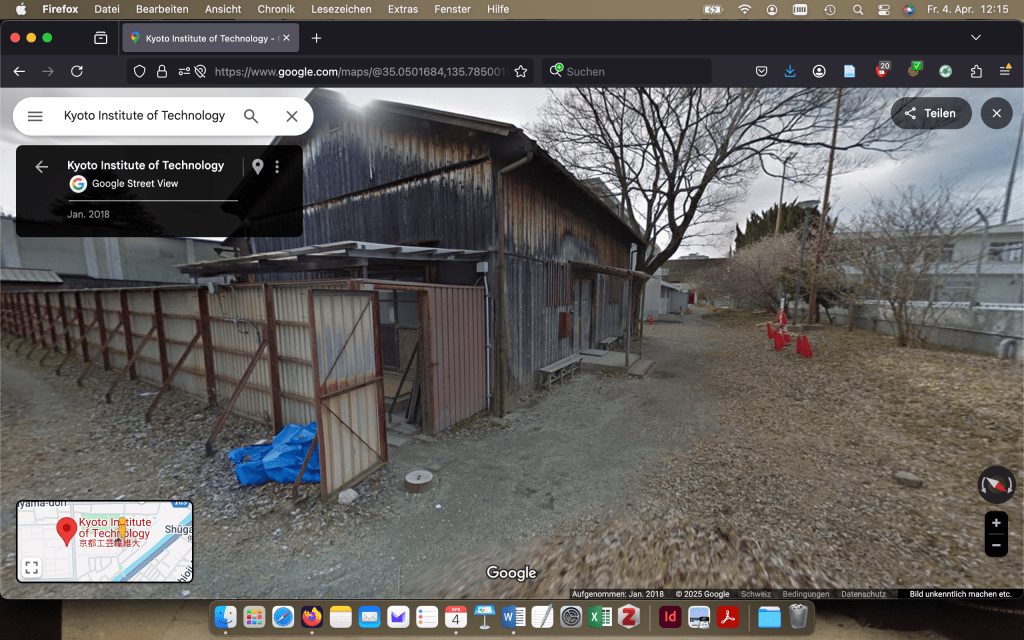

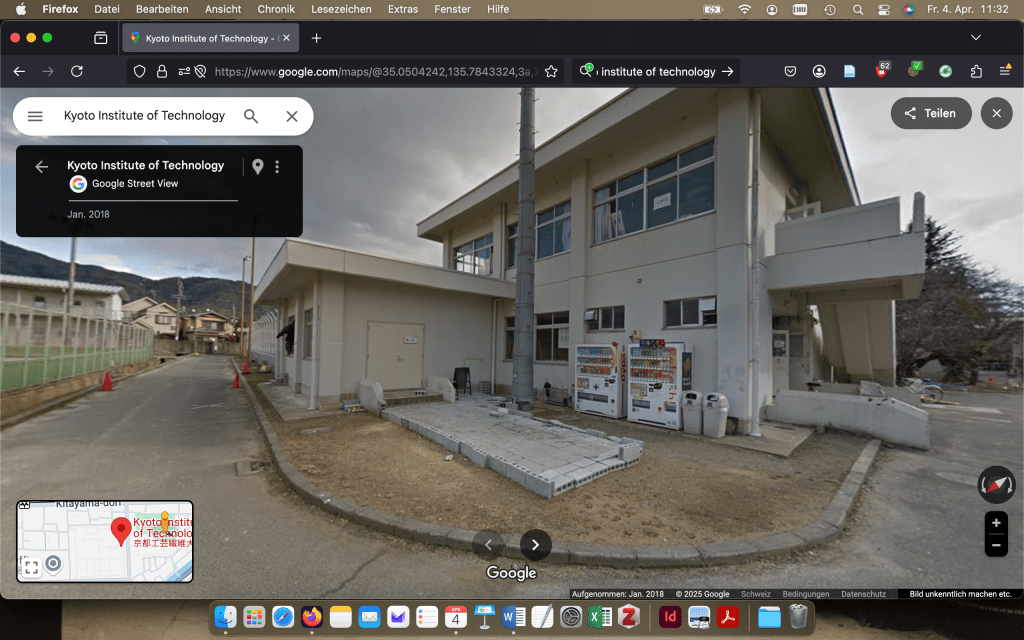

To make up for my lack of knowledge of the area, I took a virtual tour to explore its various spaces. It turns out there are lots of interesting areas that could be used for playful, collaborative activities. Some of these spaces are partially hidden or set back behind a row of trees. Although the images are a few years old, it seems that there are movable objects, such as benches and barriers designating bike parking spaces. These ‘loose variables’ encourage alternative uses of the open spaces. As with cities, the most interesting spaces on campus tend to be found on the periphery. Examples include a rustic shed, which you might not expect to find in a university setting, and a carpet of loose bricks that could be mistaken for a land art installation, contrasting with two vending machines.

Unlike my previous presentations, this one had a very practical objective. It was intended to educate the students on practical tools they could use for their assignment. I therefore organised the projects of the Stalker collective according to specific activities: stepping out, listening and observing, reimagining, playing and inviting. These actions are not arranged in any particular order, except that stepping out — crossing a physical, institutional or social boundary — is always a good place to start with these kinds of tactical, impromptu interventions in urban spaces. (I am writing about this in a forthcoming book chapter.)

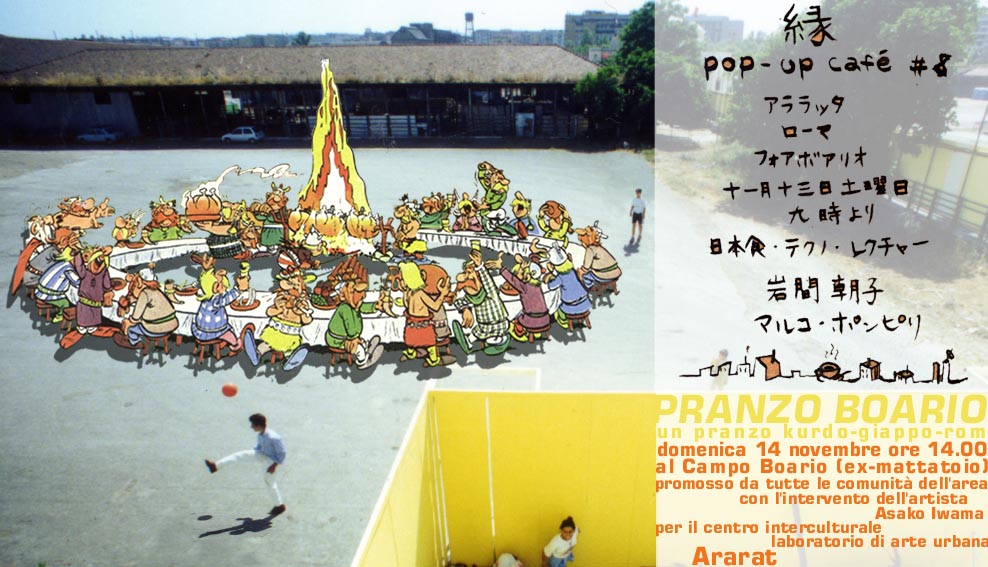

In an attempt to reduce the Eurocentrism of my research, I tried to incorporate some Japanese references. One example is Jiro Taniguchi’s Walking Man, which sensitively captures the magic of exploring the city on foot. Coincidentally, Pranzo Boario, one of Stalker’s key initiatives features Japanese ingredients. The group was planning a multicultural lunch at a former slaughterhouse to bring together the various minority groups living in the area. At the time, the food artist Asako Iwama happened to be in Rome. The Italian collective spontaneously invited her and her pop-up kitchen, resulting in a new kind of fusion cuisine: Kurdish-Romani-Japanese cuisine. “It was such an organic event,” Asako once told me, highlighting a recurring theme in Stalker’s ‘kitchen’: serendipity.

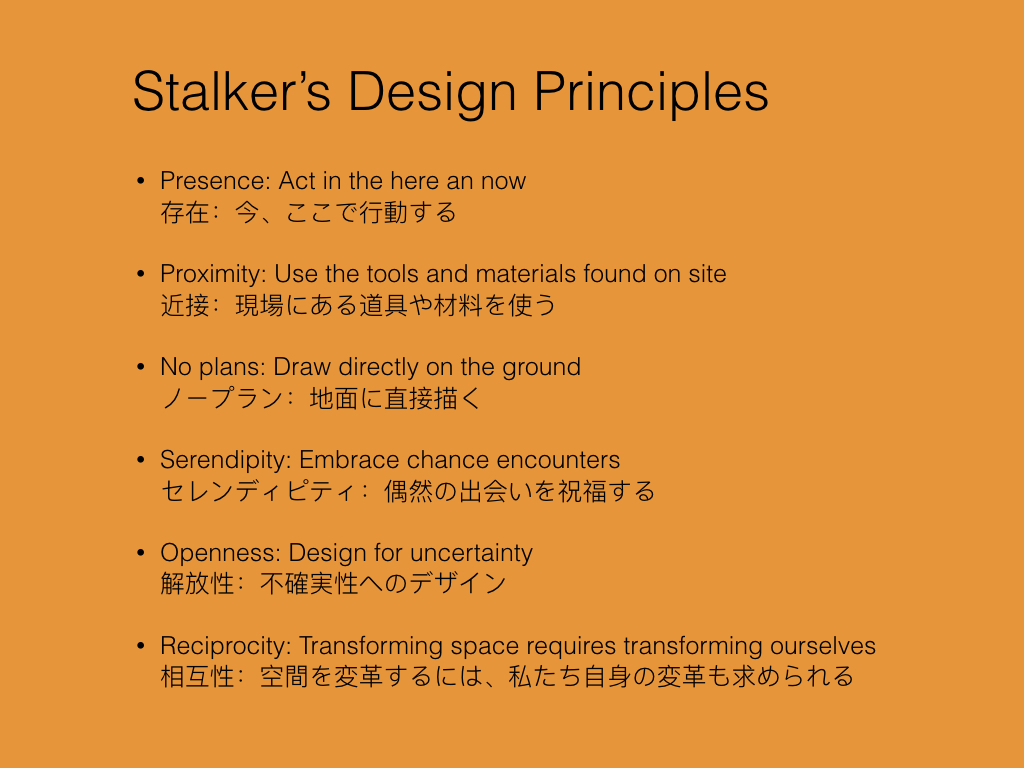

In conclusion, I identified a set of implicit design principles that characterise Stalker’s performative and socially engaged approach to transforming spaces. The students were very interested in this type of minimal intervention. To my surprise, one of them drew a comparison with traditional Japanese gardens, where serendipity is also an important design element.

A week later, a local landscape gardener presented a project for which he had used only materials found on the site. He then referred to my presentation, claiming to have adopted the ‘Stalker method’. While I was flattered, I’m sure there must be plenty of historical and contemporary examples in Japan of designers working in situ and using available materials. Nevertheless, even though this kind of knowledge may transcend cultures and geographies, relearning it will take time.

***

Postscript on yet another Japanese-Italian synergy: My friend Hayahisa Tomiyasu, the photographer who helped me with the Japanese translation, has taken an idiosyncratic look at Rome, focusing on the many poles that are missing their signs.

Leave a comment